The history of the city of Frankfurt am Main is the story of a hill at a ford in the Main that developed into a European banking metropolis, becoming the smallest metropolis in the world. The spire of the cathedral tower marks the geographical center of the city at exactly 50° 6' 42.5" North and 8° 41' 9.4" East.

Early history[edit]

Frankfurt is located in what was originally a swampy portion of the Main valley, a lowland criss-crossed by channels of the river. The oldest parts are therefore to be found on the higher portions of the valley, through which passed the Roman road from Mainz (Roman Moguntiacum) to Heddernheim (Roman Nida). The Odenwald and Spessart ranges surrounded the area, lending a defensive advantage, and placenames show that the lowlands on both sides of the river were originally wooded.

The oldest part of the Altstadt, the old city center, is the Cathedral Hill (Domhügel), upon an island created by arms of the Main. Only from the West could it be reached by foot without getting wet; this, together with its location at a ford, gave it significant military and economic advantages.

Stray archeological finds on the Domhügel go back to the Paleolithic, but the first proven settlement and land development date to the Roman era. It is assumed that the Romans settled on the hill in the last quarter of the 1st century CE; amongst other things, a Roman bath has been found, which may have belonged to a larger complex, possibly a fortress. Apparently the military occupation was abandoned during the 2nd century and replaced by a villa. Several farm buildings have also been excavated. A similar building complex was discovered at the modern Günthersburgpark in the Frankfurt-Bornheim portion of the city.

With the retreat of the Roman border to the west bank of the Rhine in 259/260, the Roman history of Frankfurt came to an end.

Early Middle Ages[edit]

The name Frankfurt first appears in writing in the year 793, but it seems to have already been a considerable city. In 794 a letter from the Emperor to the bishop of Toledo contained "in loco celebri, qui dicitur Franconofurd", which reads "that famous place, which is called Frankfurt."

It seems Cathedral Hill was already permanently settled in Merovingian times (possibly first by Romans). In 1992 excavations at the cathedral found the rich grave of a girl, that has been dated to the late Merovingian period of the 7th century.

Charlemagne built himself a royal court at "Franconovurd", the "ford of the Franks", and in the summer of 794 held a church council there, convened by the grace of God, authority of the pope, and command of Charlemagne (canon 1), and attended by the bishops of the Frankish kingdom, Italy and the province of Aquitania, and even by ecclesiastics from England. The council was summoned primarily for the condemnation of Adoptionism. According to the testimony of contemporaries two papal legates were present, Theophylact and Stephen, representing Pope Adrian I. After an allocution by Charlemagne, the bishops drew up two memorials against the Adoptionists, one containing arguments from patristic writings; the other arguments from Scripture. The first was the Libellus sacrosyllabus, written by Paulinus, Patriarch of Aquileia, in the name of the Italian bishops; the second was the Epistola Synodica, addressed to the bishops of Spain by those of Germany, Gaul and Aquitania. In the first of its fifty-six canons the council condemned Adoptionism, and in the second repudiated the Second Council of Nicaea of 787, which, according to the faulty Latin translation of its Acts (see Caroline Books), seemed to decree that the same kind of worship should be paid to images as to the Blessed Trinity, though the Greek text clearly distinguishes between latreia and proskynesis; this constituted a condemnation of iconoclasm. The remaining fifty-four canons dealt with metropolitan jurisdiction, monastic discipline, superstition etc.

Louis the Pious, Charlemagne's son, selected Frankfurt as his seat, extended the palatinate, built a larger palace, and in 838 had the city encircled by defensive walls and ditches.

After the Treaty of Verdun (843), Frankfurt became to all intents and purposes the capital of East Francia and was named Principalis sedes regni orientalis (principal seat of the eastern realm). Kings and emperors frequently stayed in Frankfurt, and Reichstags and church councils were repeatedly held there. The establishment of religious monasteries and numerous endowments to the local church furthered the urban community. Also, as the German emperor had no permanent residence anymore, Frankfurt remained the center of imperial power and the principal city of Eastern Francia.

High Middle Ages[edit]

After an era of lesser importance under the Salian and Saxon emperors, a single event once again brought Frankfurt to the fore: it was in the local church in 1147 that Bernard of Clairvaux called, amongst others, the Hohenstaufen king Conrad III to the Second Crusade. Before leaving for Jerusalem, Conrad selected his ten year-old son as heir, but the boy died before his father. Due to this, an election was held in Frankfurt five years later, and after the emperor Frederick Barbarossa was elected, Frankfurt became the customary place for the election of the German kings.

Under the Hohenstaufen emperors, Frankfurt experienced strong growth and rising national importance. By 1180 the city had expanded greatly, and by 1250 had seen an increase in privileges in addition to economic growth. Police power in the city lay in the hands of the bailiffs and reeves; however, the citizens selected their own mayors and officials, who were responsible for police management and some judicial duties. These officials enjoyed the favor of the emperors, who had eliminated the reeves entirely by the end of the Hohenstaufen dynasty.

Frankfurt preserved its essentially medieval aspect as late as 1872

The Early Modern era, 16th to 18th centuries[edit]

Starting from the 16th century, trade and the arts flowered in Frankfurt. Science and innovation progressed, and the invention of the printing press in nearby Mainz promoted education and knowledge. From the 15th to 17th centuries, the most important book fair in Germany was held in Frankfurt, a custom which would be revived in 1949.

In the early 17th century tensions between the guilds and the patricians, who dominated the city council, led to substantial unrest. The guilds asked for greater participation in urban and fiscal policies as well as for economic restrictions of the Jewish community's rights. In 1612, after the election of Emperor Matthias the council rejected the Guild's request, to read out publicly the imperial privileges given to the city. This caused the so-called Fettmilch Rebellion, named after its leader, the baker Vinzenz Fettmilch. A part of the populace, mainly craftsmen, rose up against the city council. In 1614, the mob began a pogrom in the city's Jewish ghetto, and the emperor had to ask Mainz and Hessen-Darmstadt to restore order.

In the Thirty Years' War, Frankfurt was able to maintain its neutrality; the city council had avoided siding with one opponent or another after its negative experiences in the Schmalkaldic War. This issue became critical between 1631 and 1635, when the Swedish regent Gustav Adolf came to Frankfurt demanding accommodation and provisions for himself and his troops. But the city mastered these adversities more easily than what was to follow the war: the plague ravaged the city, as it would most of Europe at this time. In the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, Frankfurt was confirmed as an Imperial Free City, and soon reached new heights of prosperity.

Frankfurt in 1770, protected by its walls and

bastions

From the French Revolution to the end of the Free State[edit]

During the French Revolutionary War, General Custine occupied Frankfurt in October 1792. On December 2 of the same year, the city was retaken.

In January 1806, General Augereau occupied the city with 9,000 men and extorted 4 million francs from it. Frankfurt's status as a free city ended when it was granted to Karl Theodor Anton Maria von Dalberg in the same year. In 1810 Dalberg's territories were reorganized into the Grand Duchy of Frankfurt.

During this time, the city experienced serious changes in the structure and construction of the town. Centuries-old defensive walls were dismantled, replaced by garden plots. It was felt that one no longer need fear cannon fire, even without walls. On July 1, 1808, Goethe's mother wrote to her son Wolfgang: "Die alten Wälle sind abgetragen, die alten Tore eingerissen, um die ganze Stadt ein Park." (The old barriers are threadbare, the old gates torn down, around the whole city a park.)

On November 2, 1813, the allies drew together in Frankfurt, to re-establish its old rights and set up a central administrative council under Baron vom Stein. The Congress of Vienna clarified that Frankfurt was a Free City of the German federation, and in 1816 it became the seat of the Bundestag. This government seat occupied the Palais Thurn und Taxis. When Goethe visited his native city for the last time in 1815, he encouraged the councilmen with the words: "A free spirit befits a free city…..It befits Frankfurt to shine in all directions and to be active in all directions."

The city took good heed of this advice. When in 1831 Arthur Schopenhauer, a lecturer at the time, moved from Berlin to Frankfurt, he justified it with the lines: "Healthy climate, beautiful surroundings, the amenities of large cities, the Natural History Museum, better theater, opera, and concerts, more Englishman, better coffee houses, no bad water… and a better dentist."

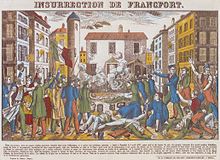

In 1833 a revolutionary movement attempted to topple the Diet of the royalist German Confederation, which sat at Frankfurt, and was quickly put down. [1]

Rebellion of the German Revolutionary Student Movement, 1833

The Revolutions of 1848 and their aftermath[edit]

The Revolutions of 1848, also known as the March Revolution, forced Klemens von Metternich, the reactionary Austrian head of state, to step down. This was celebrated wildly in Frankfurt. On 30 March 1848 one could see black, red, and gold flags everywhere, and the populace was admonished not to shoot into the air.

On 18 May 1848, a day which some historians[who?] call the greatest day in the history of the city, the National Assembly held its first meeting in the Frankfurter Paulskirche. The last meeting was held there a year later, on 31 May 1849. Frankfurt was at this point the center of all political life in Germany. The party transformation and the excitement were the most violent there; riots, particularly among those living in the Sachsenhausen quarter, had to be suppressed with force of arms on 7–8 July 1848 as well as on 18 September.

The next fifteen years saw new industrial laws focusing on complete freedom of trade, and political Emancipation of the Jews, initiated ten years before its final realization in 1864.

Starting in August 1863, a political gathering focused on German federal reform met in Frankfurt, including the national congress and the opposing reform congress. The Kingdom of Prussia did not show up, however, and the reform failed, leading to the Austro-Prussian War in 1866. Frankfurt was annexed by Prussia as a result of the war, and the city was made part of the province of Hesse-Nassau.

Recent history[edit]

Early Nazi period[edit]

In 1933 the Jewish mayor (Oberbürgermeister) Ludwig Landmann was replaced by NSDAP member Friedrich Krebs. This led to the firing of all Jewish officials in the city administration and from city organizations. A meeting of Frankfurt traders, who wanted to discuss the boycott of Jewish businesses, was broken up and the participants arrested and intimidated. Although the Nazis had originally mocked the city as the Jerusalem am Main because of its high Jewish population, the city adopted a propagandistic nickname, the Stadt des deutschen Handwerks or the city of German craft.

Kristallnacht[edit]

Most of the synagogues in Frankfurt were destroyed by the Nazis on Kristallnacht in late 1938, deportation of the Jewish residents to their deaths in the Nazi concentration camps quickening in pace after the event. Their property and valuables were stolen by the Gestapo before deportation, and they were subjected to extreme violence and sadism during transport to the train stations for the cattle wagons which carried them east. Most later deportees (after the war began in 1939) ended up in new ghettoes established by the Nazis such as the Warsaw Ghetto and the Lodz ghetto, before their final transportation and murder in camps such as Sobibor, Belzec and Treblinka.

World War II[edit]

Model of Frankfurt's old city center after the bombing raids.

Large parts of the city center were destroyed by in the bombings of the second World War. On March 22, 1944, a British attack destroyed the entire Old City, killing 1001 people. The East Port - an important shipping center for bulk goods, with its own rail connection - was also largely destroyed.

Frankfurt was first reached by the Allied ground advance into Germany during late March 1945. The US 5th Infantry Division seized the Rhine-Main airport on 26 March 1945 and crossed assault forces over the river into the city on the following day. The tanks of the supporting US 6th Armored Division at the Main River bridgehead came under concentrated fire from dug-in heavy flak guns at Frankfurt. The urban battle consisted of slow clearing operations on a block-by-block basis until 29 March 1945, when Frankfurt was declared as secured, although some sporadic fighting continued until 4 April 1945.[2]

Post-war period[edit]

The Military Governor for the United States Zone (1945–1949) and the United States High Commissioner for Germany (HICOG) (1949–1952) had their headquarters in the IG Farben Building, intentionally left undamaged by the Allies' wartime bombardment[citation needed]. The heavily destroyed city decided in the spirit of the time to plan a major reconstruction of the historical city center, retaining the old road system. The formerly independent city republic joined the state of Hesse in 1946. As the state capital was already at the smaller city of Wiesbaden and the American armed forces had used Frankfurt as their European headquarters, the city seemed most promising candidate for the West German federal capital. The American forces even agreed to withdraw from Frankfurt to make it suitable, as the British forces already had withdrawn from Bonn. Much to the disappointment of many in Frankfurt, however, the vote narrowly favored Bonn twice. Despite this, the mayor looked towards the future, seeing that with the division of Germany and relative isolation of Berlin, Frankfurt could take over positions in trade and commerce previously filled by Berlin and Leipzig. Since Bonn never played an important role despite its status as capital, Frankfurt, Hamburg, and Munich realigned themselves, passing from regional centers to international metropolises and effectively forming three West German cultural and financial capitals.

Since the turn of the 2nd century, the Frankfurt fair has been held every fall and had become the most important fair site in Europe. Frankfurt's countless publishing houses as well as its fur industry profited from the elimination of Leipzig by the division of Germany into East and West. After the war, the West German book fair was held in Frankfurt. Since German reunification, the Frankfurt Book Fair is held in the fall, and Leipzig's in the spring. The bi-annual Internationale Automobil-Ausstellung is a worldwide car fair that is also held in Frankfurt.

The Deutsche Bundesbank made Frankfurt its seat, and most major banks followed suit. This and the Frankfurt Stock Exchange have made the city the second most important commercial center in Europe, after London.

Jewish Frankfurt am Main[edit]